No one understood the implications of Mahan

and Turner better than Theodore Roosevelt, who in a brief but vigorous lifetime

had direct experience both in the frontier West and in the Navy Department. To

Roosevelt the prospect of America isolated and confined in a world of predator

nations was anathema. Together with Lodge, Secretary of State John Hay, and a

handful of others in government, Howard Beale has observed, he “plunge[d] the

nation into an imperialist career” in 1898 “that it never explicitly decided to

follow.” The pugnacious young “TR” believed that a man just wasn’t a man

without a six-gun and a nation just wasn’t a nation without a fleet of

battleships. Should the nation be forced to go to war with either European

meddlers or hemispheric predators, a large steel-clad, big-gun navy, he argued,

would allow it to emerge “immeasurably the gainer in honor and renown. . . . If

we announce in the beginning that we don’t class ourselves among the really

great peoples who are willing to fight for their greatness, that we intend to

remain defenseless, . . . we doubtless can remain at peace,” but “it will not

be the kind of peace which tends to exalt the national name, or make the

individual citizen self-respecting.” In an amoral world of nations maneuvering

incessantly for power, prestige, and position, peace could be preserved only by

periodic threats of sword and gun. “If we build and maintain an adequate navy

and let it be understood that . . . we are perfectly ready and willing to fight

for our rights, then . . . the chances of war will become infinitesimal.”

But the navy could not be simply defensive

and reactive; it had to be the spearhead of a vigorous, healthy national empire

that stretched to the ends of the earth. “Every expansion of a great civilized

power,” Roosevelt wrote at the end of 1899 in a typically Mahanian tone,

means

a victory for law, order, and righteousness. This has been the case in every

instance of expansion during the present century, whether the expanding power

were France or England, Russia or America. In every instance the expansion has

been of benefit, not so much to the power nominally benefited, as to the whole

world. In every instance the result proved that the expanding power was doing a

duty to civilization far greater and more important than could have been done

by any stationary power.

Although Europeans that year generally

viewed the upstart Yankees as bullies who exploited Spanish imperial weakness

to grab a modest Asian and Caribbean empire, the citizens of the United States

were convinced that they had rescued the hapless peoples of Cuba, Puerto Rico,

the Philippines, and even Guam from the yoke of oppression and that the navy

had been the chief instrument of righteousness. All the nightmarish scenarios

of helpless men in thrall to whimsically exploding machines that had emerged

from the Sino-Japanese conflict evaporated during the euphoria of victory in a

“splendid little war” over a chivalrous if incompetent and often disheartened

opponent.

Unlike the earlier clash off the China

coast, the Spanish-American War was fully reported throughout the Western world

and thus became the first naval conflict of the industrial age that both the

public and the experts understood. The dominant perception was of industrial

man’s mastery of his creations. Well-handled warships run by well-trained crews

were no menace to anyone but their enemies. Such an impression helped stifle

initial public concern in the United States and abroad that the loss of Maine

might have been due to faulty industrial technology. The ensuing naval triumphs

over Spain convinced the Americans and Europeans that the ship’s destruction

had been an act of Spanish sabotage.

Although in 1898 shipborne radio was still

some years in the future, “for the first time in naval history, a government

directed the action of distant ships at sea, communicating by telegram” to

Commodore George Dewey at Hong Kong and later Manila and to Admiral William T.

Sampson and Commodore Winfield S. Schley at Key West and Cuba. When Sampson

finally found Admiral Pascual Cervera’s fleet huddling inside Santiago harbor,

he ordered that his major warships take turns illuminating the channel at night

with searchlights. “It was the first such use of light by naval forces.”

But contemporary observers were less

impressed with the use of the new technology of electricity for communication

and illumination than with the overall power of the modern warship and, above

all, the technical competence displayed by the American seamen in running it

efficiently. At Manila Bay, Dewey coolly brought his small squadron through the

minefield off Corregidor in the dead of night and early the next morning

quickly maneuvered his handful of steel and steam cruisers and lesser war craft

into a coherent battle line against the few enemy warships lurking behind the

guns of the narrow Cavite Peninsula. Already under steady but wildly inaccurate

bombardment, Dewey calmly informed Olympia’s captain, “You may fire when ready,

Gridley,” and after seeing his gunners methodically pulverize the enemy, he

withdrew and sent the men to breakfast. The supposedly hellish elements of the

battle—stokers locked and crammed into dark, feverishly hot propulsion

compartments with hissing steam pipes, clattering engines, and roaring

furnaces—in fact did not bother the men involved at all. According to one participant,

the engine-room crew aboard the cruiser Baltimore spent the time when not

engaged in answering orders and moving dials smoking cigars, chewing tobacco,

and “swapping yarns.” Only one man died (an engineer suffered a heart attack),

a few wounded, and the casualties were understandably obscured by total

victory.26 Thousands of miles from home and help, Dewey nonetheless proceeded

to fend off by bluff and bluster the handful of European warships that soon

arrived to scrounge for any potential imperial scraps they could lap up, thus

preserving Manila Bay and the entire Philippine archipelago for Yankee

occupation.

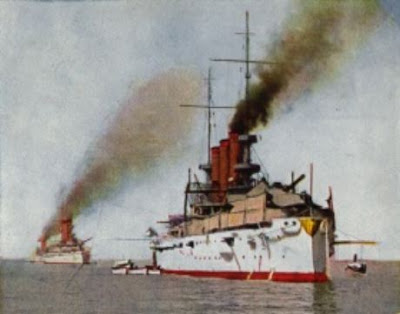

Off Santiago some weeks later, Schley ably

handled his small squadron of battleships and cruisers. As Vice Admiral Pascual

Cervera y Topete’s cruisers emerged from the harbor, Schley chased them down

and mortally wounded them one by one after a spirited run that in this instance

did demand the final ounces of energy from the poor devils who toiled away

passing coal and tending boilers in the engine rooms of Iowa, Indiana, Oregon,

Texas, New York, and Brooklyn. When the last Spanish cruiser captain

despairingly crashed his vessel against the rocks of eastern Cuba, America had

won itself a modest Caribbean empire to go with its new holdings in East Asia.

Almost as an afterthought, Washington finally annexed the Hawaiian Islands,

which had been under the control of a planter “republic” for the previous five

years.

The same American writer who only weeks

before had questioned the safety of battleships was now ecstatic. “Military

prowess passed away from Spain many years ago, and her organization to manage

the modern ship, composed principally of machinery, is wretchedly deficient,”

Hollis told his readers. The U.S. Navy, on the other hand, understood the value

of “education and technical training to a specific end” and had triumphed.

Sailors, officers, and marines had performed superbly in their highly technical

tasks of machine tending. If the war with Spain had demonstrated anything it

was that the United States needed more battleships of every type. The cost

would be high, but “these ships are well-nigh impregnable, and they must

continue to hold their own as our main reliance for offense and defense.”

No comments:

Post a Comment